10 Nov 2021

Help! It’s an emergency – procedure for nursing ECC patients

Victoria Bowes outlines what to do when attending an emergent patient, focusing on the importance of triage.

Image: GaiBru Photo / Adobe Stock

When clients attend the clinic in an emergency, it is important their animal is received and acknowledged on arrival. One must remember that owners are likely to be in a state of distress at this point, so significant communication impacts may exist.

It is with the use of careful questions and supportive care that the key information needed can be gained from the client. Gaining as much information on the original telephone call can enable a faster response for the patient when it arrives.

It would be useful to ensure all reception staff are trained in emergency situations and how best to communicate, ensuring a better outcome for the patient.

Triage

Triage is the system of organising patients according to their condition risk and severity. This is mainly used to ensure patients are seen within an appropriate time frame. Triage, as a system, was created during the First World War when assessing injured soldiers in the battlefield.

Triage assessment starts with the assessment of the three main body systems – circulatory, respiratory and neurological are to be observed at the point of triage (Covey, 2018). After this has been assessed, the secondary survey will aid in further assessing other body systems.

Various triage systems exist that would be appropriate for use in the veterinary practice. These may include:

- Veterinary triage list as developed by Ruys et al (2012).

- The animal trauma triage system (Covey, 2018).

Primary survey

The primary assessment should be completed on arrival to the veterinary clinic. The staff must be prepared and ready as most injuries will be time-dependent. Veterinary staff must remember the key aims of first aid at all times – preserve life, prevent suffering and prevent the situation deteriorating.

Poli (2017a) suggested using the pneumonic ABCDE to complete the primary survey of the patient and observing any critical indicators of health:

- Airways

- Breathing

- Circulation

- Disability (neurological)

- External

Using this pneumonic, staff can initially try to stabilise the patient and complete the initial assessment, therefore enabling staff to complete further assessments as part of the secondary survey.

Secondary survey

The secondary survey is completed when the patient is stabilised and should not be started until this point. Poli (2017b) discusses that the secondary survey will help identify any other issues that may not have been picked up on the primary survey. The pneumonic used for secondary surveys is A CRASH PLAN:

- Airway

- Cardiovascular

- Respiratory

- Abdomen

- Spine

- Head

- Pelvis

- Limbs

- Arteries

- Nerves

Once the primary and secondary survey has been completed, the patient may require admitting to the hospital for intensive critical care monitoring.

Monitoring the critical inpatient

When a patient is admitted for intensive critical care monitoring, the monitoring provided has to be continuous and careful, and patient‑specific. It must be remembered that every patient is different, and has different care needs and requirements.

The monitoring of the patient should be completed hands-on, with no reliance on the use of equipment. When completing hands-on assessments, this allows prompt recognition of any clinical changes.

All the body systems will need to be monitored; this will be via clinical assessment and monitoring equipment. While useful, limitations exist of monitoring systems that are important to be cognisant of, as invasive monitoring may have potential negative consequences in a critically ill patient (Pachtinger, 2013).

The following systems should be monitored.

Cardiovascular

When monitoring the cardiovascular system, the following should be observed:

- heart rate and rhythm

- pulse points

- pulse quality

- mucous membrane colour

- capillary refill time

The patient should also be monitored with electrocardiography (ECG). This can help identify any pre-existing cardiac disease, metabolic disorder and any possible arrhythmias. If indication of arrhythmia or changes are evident in the rate or rhythm, the information provided should be carefully studied to determine possible causes.

Continuous ECG is useful for patients with dysrhythmias or those with rapidly changing heart rates. It is also indicated for monitoring patients with intracranial disease or electrolyte abnormalities, such as hyperkalaemia (Andrews-Jones, 2012). The information should be reported to the veterinary surgeon immediately, to provide further treatment or possible medications.

Respiratory

Observing the respiratory system may be best completed while the patient is undergoing triage.

Stress and possibly separation anxiety from the owner may also impact the patient’s respiratory function. When observing the respiratory system, the following is monitored:

- Breathing patterns – is the patient taking regular breaths? Is the pattern consistent? Is it shallow or deep? Mouth breathing should be monitored, and any signs or orthopnoea should be reported immediately. With severe respiratory distress, paradoxic respiration may be seen. This is when the chest wall and abdominal wall move in opposite directions (Pachtinger, 2013).

- Body posture – when a patient is suffering respiratory distress, changes to the body posture may be evident. The patient’s head and neck may be extended, and may have elbow abduction. This allows the patient to expand the respiratory area and reduce chest compression.

Other monitoring methods that may be considered include:

- Pulse oximetry is a non-invasive assessment of oxygen levels in the circulating blood. This is completed by placing the monitor on mucous membrane, which provides an estimation of the levels of haemoglobin saturation.

- Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis is defined as the gold standard of direct assessment of pulmonary function (Pachtinger, 2013). The blood is commonly taken from the dorsal pedal artery, and many newer machines may provide additional blood assessments such as lactate or electrolytes. Venous blood sampling may need to be considered if arterial is not suitable. ABG provides key information on metabolic acid base state of the body. This can provide results that may need immediate treatment – especially for some metabolic disorders that may be presented.

- Lactate is also part of the routine monitoring of critical inpatients and provides information on the current cardiovascular functioning of the patient. Monitoring of lactate can enable prompt identification of hypoperfusion. If identified, the cause and possible treatment should be reported to the veterinary surgeon.

Neurological

The neurological system must be monitored alongside other systems, as any change in another body system can have resulting neurological changes.

When assessing and monitoring the system, the Modified Glasgow Coma Scale should be completed during the initial assessment and continually as an inpatient. The following should be observed:

- Mentation – is the patient alert, responsive, obtunded, stuporous or possibly comatose? Alongside this assessment, gait and movement can be observed.

- Blink (menace) reflex.

- Any nystagmus, strabismus.

- Pupil – size, symmetry, pupillary light reflex.

- Gag reflex.

- Pain sensation and reflex tests (Andrews-Jones, 2012).

Careful monitoring and continuous assessment should be completed if head trauma is suspected, as changes in intracranial blood pressure can cause significant brain damage.

When nursing patients with a suspected head trauma, where no other suspected head or vertebral damage exists, the head should be elevated to 30°. This will allow venous return and hopefully reduce intracranial pressure (Farry, 2012).

Temperature should be monitored and recorded regularly, with consideration given to patients that may have limited anal tone for rectal temperatures as this can be affected by the lack of tone.

Blood pressure is monitored in the critical patient, as it is a very reliable assessment of the patient’s cardiovascular function and tissue perfusion. If changes to levels indicating either hypotension or hypertension are evident, this should be investigated immediately. Identifying possible causes allows the veterinary surgeon to prescribe appropriate treatments. Blood pressure can be observed via direct or indirect assessment.

Direct assessment is the use of a catheter placed in a peripheral artery – most commonly the dorsal pedal. This is then connected to monitor and transducer.

Indirect monitoring is via the use of either oscillometry or Doppler.

Oscillometry is the use of a machine that inflates a cuff and slowly releases it, allowing for the detection of the pulsating changes.

Doppler is the use of an ultrasonic flow monitor. A piezoelectric probe is placed over a peripheral artery and a cuff inflated, with the sound changes monitored and recorded as appropriate.

Central venous pressure measures the blood pressure in the central venous compartment – usually via a catheter in the jugular vein (Andrews-Jones, 2012). This is a useful tool to assess the current blood volume and possible volume overload.

Pain

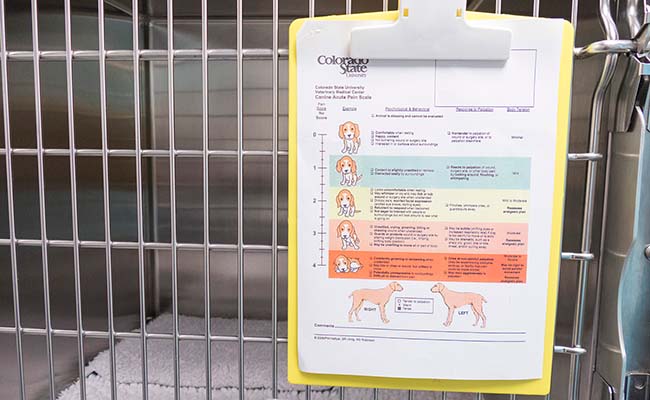

The patient should be monitored regularly for pain and this should be completed by using one of the recognised pain assessment scores.

Grimace scores are also available to be used in other species, where some pain indicators are not as clear.

Pain management is imperative in the critical impatient, as pain responses can impact various areas of the body systems.

Urine output

Urine output is a key indicator for renal health. Output should be 1ml/kg/hr to 2ml/kg/hr, and should be monitored and recorded every two hours.

A closed urinary catheter collection system is a good tool to allow monitoring of urine output, but also to reduce the risk of urine scolds.

One must be aware that an increase in urine production may be seen with the use of IV fluid therapy.

Nursing care

This article has covered triage and elements of monitoring the critical inpatient. Many monitoring methods should be used in critical and intensive care nursing, and these will be different for each patient admitted.

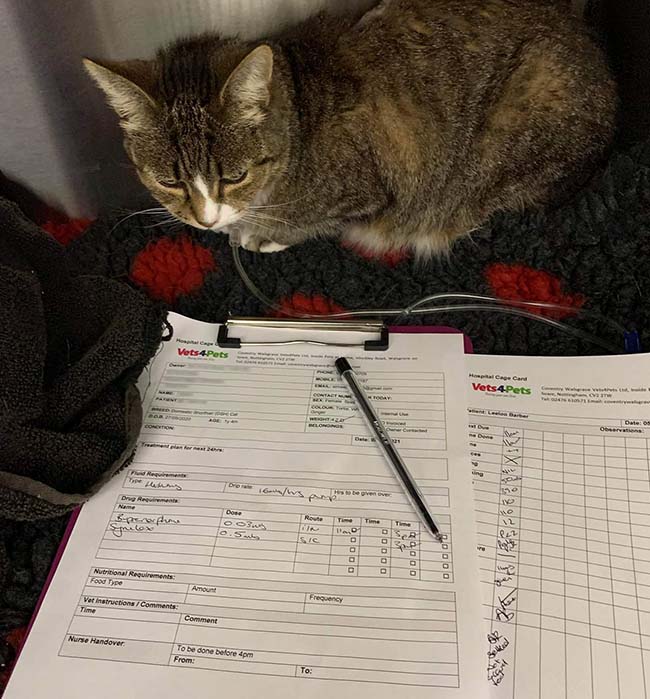

Each patient will have a series of set individual nursing needs. It is extremely important to complete a thorough patient assessment form, as the nursing can then be planned and implemented using a nursing care plan.

Veterinary nurses should continually research standards and techniques via evidence‑based veterinary nursing, ensuring accurate and appropriate nursing standards are delivered.

A high standard of hygiene is imperative – and everything completed should be recorded along with standard monitoring. The use of nursing care plans will support effective monitoring systems.

When handing patients over to other staff, time should be given to ensure a thorough patient handover has been completed for an effective outcome for the patient.

References

- Andrews-Jones B (2012). Monitoring the critically ill patient, WSAVA/FECAVA/BSAVA World Congress 2012 (accessed 14 September 2021).

- Covey E (2018). How to triage, Vet Nurse 9(5): 262-268.

- Farry T (2012). Monitoring the critical patient. In Norkus C (ed), Veterinary Technicians Manual for Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care (1st edn), Wiley‑Blackwell, Chichester: 63-81.

- Linklater A (2020). Monitoring the critically ill animal using the rule of 20, emergency medicine and critical care, MSD Veterinary Manual (accessed 1 October 2021).

- Pachtinger G (2013). Monitoring of the emergent small animal patient, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 43(4): 705-720.

- Poli G (2017a). Triage, pt 1: primary survey, Vet Times (accessed 19 September 2021).

- Poli G (2017b). Triage, pt 2: secondary survey, Vet Times (accessed 15 September 2021).

- Ruys LJ, Gunning M, Teske E et al (2012). Evaluation of a veterinary triage list modified from a human five-point triage system in 485 dogs and cats, J Vet Emerg Crit Care 22(3): 303-312.

Meet the authors

Victoria Bowes

Job Title