17 Sept 2024

Room for improvement exists when it comes to practising cleanliness around collecting and feeding colostrum, so vets must engage with clients about keeping equipment for feeding calves clean and establishing an effective standard operating procedure on farm.

Feeding equipment needs to be stored off the floor after cleaning.

Diseases in young calves, such as pneumonia and diarrhoea, are usually caused by a deficient immune system and a high pathogen load (Murray et al, 2016).

Vets are now regularly involved in the monitoring of the transfer of passive immunity on many farms through the use of serum refractometry or other testing modalities.

Through industry initiatives such as #Colostrumisgold, farmers are, in general, now well aware of the importance of colostrum and the need to get sufficient good quality colostrum into calves as quickly as possible after birth.

It is the author’s experience, however, that room for improvement often still exists in the hygiene practices around the collection and feeding of colostrum.

Bacterial contamination of colostrum can be caused by inadequate udder preparation during collection, contamination of the equipment used for collecting, storing or delivering the colostrum to the calf, as well as improper storage. It is associated with decreased absorption of antibodies due to interaction between bacteria and antibodies (Godden et al, 2019), as well as being a potential source of direct transmission of pathogens.

As we move past colostrum feeding and into the feeding of milk, or milk replacer, the issue of hygiene remains, with studies reporting high levels of bacterial contamination of feeding equipment enhancing the spread of pathogens among calves (Heinemann et al, 2021).

Irregular or inadequate cleaning is one of the most common problems in calf rearing, and implementing appropriate cleaning and management interventions are key tools for disease prevention by avoiding the transmission of infectious agents (Barry et al, 2019).

Heinemann et al (2021) highlighted the need for vets to regularly draw farmers’ attention to the importance of hygiene in calf rearing by pointing out weak points and then providing practical advice on improvements that can be easily implemented.

Through this article, we will focus on the hygiene of equipment used for the feeding of calves and look at some of the opportunities for us to engage with our clients on this topic.

Poorly maintained feed equipment is harder to clean.

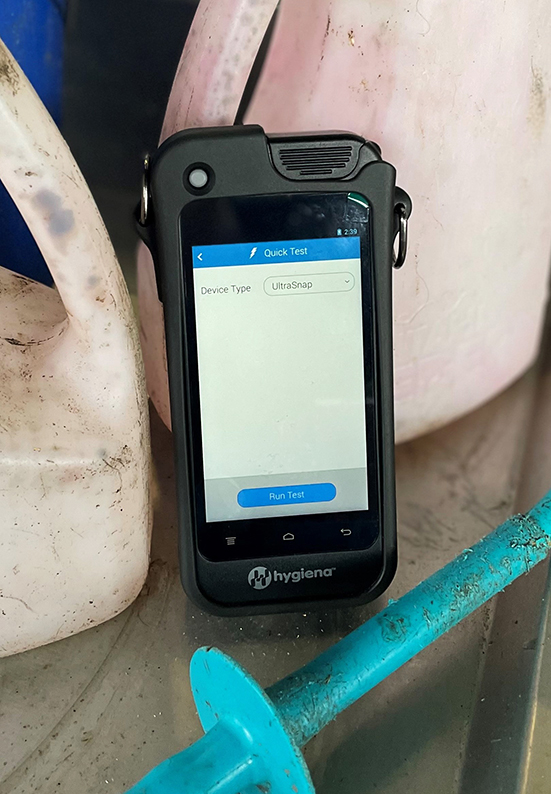

Handheld ATP monitors can provide rapid assessment of the effectiveness of cleaning protocols.

To be able to provide advice, it is essential for us to fully understand exactly what is going on the farm.

For farms calving animals and feeding colostrum, the hygiene assessment needs to start with the collection and storage of the colostrum, and then move on to how it is fed to the calves and all subsequent milk feed preparation and administration equipment.

For calf rearers, the focus will be on all the equipment used in the preparation and delivery of milk feeds.

For all farms, do not overlook equipment that is only used occasionally (such as stomach tubes or bottles, and teats used for sick calves), as these are items used on the highest-risk animals and can often be forgotten as part of the regular cleaning regime.

As for all good clinical work-ups or disease investigations, it is essential for us to move away from asking closed questions, ensuring the questions we ask are open and will provide a complete picture of what goes on at calf level. Simply asking “Is your feeding equipment regularly cleaned?”, provides the opportunity for the conversation to be shut down almost immediately with a positive affirmation, which gives us no detail on the frequency or the process of the cleaning.

Instead, it is important to get into the detail of what actually happens and when. We need to understand the frequency of cleaning, what temperature the water is and what, if any, chemicals are used and at what concentration.

It is also important to speak to everyone involved with calf feeding, as it is not unusual for variations to exist in protocols between team members. Open discussion about cleaning protocols can often shed light on significant inconsistencies between the team members or highlight easy points for improvement, and provide the veterinary surgeon with the opportunity to provide an agreed standard operating procedure (SOP) for the farm to work to.

Panel 1 provides an overview of the key steps that should be addressed in the cleaning of calf-feeding equipment.

1. Rinse using warm water (approximately 32°C to 38°C), rinse dirt and milk residues off both the inside and the outside of the feeding equipment. Do not use hot water at this stage, as that will cause the fat and protein to stick to the equipment.

2. Soak equipment in hot water (54°C to 57°C) with a chlorinated alkaline detergent. Soak for at least 20 to 30 minutes.

3. Scrub using a brush, clean all surfaces to loosen remaining residues.

4. Wash all of the feeding equipment in hot water (at least 50°C) to remove any remaining residues.

5. Rinse again. Rinse the inside and outside of feeding equipment again using an acid sanitiser. This lowers the surface pH and makes it very difficult for any remaining bacteria to thrive.

6. Dry. Allow the equipment to drain and dry before using again. Equipment should be hung up or left on drying racks to dry thoroughly. Avoid stacking buckets inside each other and certainly do not place feeding equipment upside down on a concrete floor, because this will inhibit proper drying and drainage and provide bacteria with the perfect environment to multiply.

The provision of an objective assessment of equipment cleanliness is a key step in engaging with clients on the important topic of hygiene, and being able to assess the impact of changes in management procedures and protocols.

Visual inspection of feeding equipment using scoring systems, such as that outlined in Table 1, can help provide a rapid, objective assessment and can be used to highlight specific areas that need better attention. They are often useful during initial visits or disease investigations, where they can be used to highlight equipment in need of cleaning.

| Table 1. Visual hygiene assessment scoring system used to assess contamination of feeding equipment (Renaud et al, 2017) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Overall hygiene score | Milk/colostrum | Faecal material |

| 1 | Feeding equipment is visibly clean (no faecal material or milk/colostrum debris residue) | No milk/colostrum debris residue is visible | No faecal material is visible |

| 2 | Trace amounts of manure, milk/colostrum residue, or both, are visible | Trace amounts of milk/colostrum residue are visible | Trace amounts of manure residue are visible |

| 3 | Manure, milk/colostrum residue, or both, is clearly visible | Milk/colostrum residue is clearly visible | Manure is clearly visible |

| 4 | Manure contamination, milk/colostrum residue, or both, is extensive | Milk/colostrum residue is extensive | Manure contamination is extensive |

Visual scoring systems are of limited use in the assessment of the effectiveness of cleaning practices, as they do not provide information on the level of bacterial contamination on visibly clean surfaces.

Direct swabbing or sampling of the feeding or milking equipment surfaces, to quantify bacterial contamination using classic microbiological culture, is still considered the gold standard method, but gives delayed results and can be cost prohibitive for inclusion in the routine monitoring of on-farm cleaning practices. More recently, the rapid assessment of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) found on different surfaces has begun to be used on farm as an indirect tool for the quantification of bacterial contamination. The monitoring of ATP is already widely used as a standard approach in the medical and food industries where ATP, due to bacterial activity on the sampled surface, is quantified using a bioluminescence assay and then generally tested in a portable device. The result is displayed in relative light units a few seconds after the swabbed material has been in contact with luciferase, an enzyme which chemically generates light, meaning an objective result is available within 30 seconds of sampling a surface.

Such rapid turnaround of sampling means a discussion can be had there and then about the result, increasing the engagement with the client. With the cost of the swabs being only a couple of pounds, it is also possible to build regular hygiene assessment into calf health monitoring programmes.

Visual assessment of feeders can often identify areas where cleaning protocols aren’t up to scratch.

Feeding equipment needs to be stored off the floor after cleaning.

So, what are the common issues identified? While no two farms are the same, it is the author’s experience that some common issues exist in terms of hygiene of calf feeding equipment.

For colostrum feeding, always check how colostrum is collected and stored. Is dedicated equipment for colostrum harvesting used and is that equipment fully cleaned in line with the normal milking parlour hygiene protocols after every use? For all feeding equipment, an SOP for its cleaning should be in place that everyone knows and follows.

The lack of a standardised plan can lead to variation among team members and a breakdown in hygiene protocols. Making the cleaning process easy will increase the chances of it being done properly, and poor set-ups or lack of the essential equipment are barriers frequently seen on farm.

It is essential that the team is provided with adequate supplies of water at the correct temperature, the correct chemicals and the means to measure them out to the right concentration, cleaning equipment such as brushes, and a decent wash trough with good drainage.

It is also important that places exist to hang everything up off the floor to drain and dry. How often have you seen freshly cleaned feeding troughs or buckets placed on a dirty floor to dry? This practice rapidly undoes even the best cleaning protocol and needs to be avoided.

A David Weaver

Job Title